a lot of new projects in various stages of design, permitting and construction

Projects in development

We have a number of interesting projects in process right now - great clients, great sites.

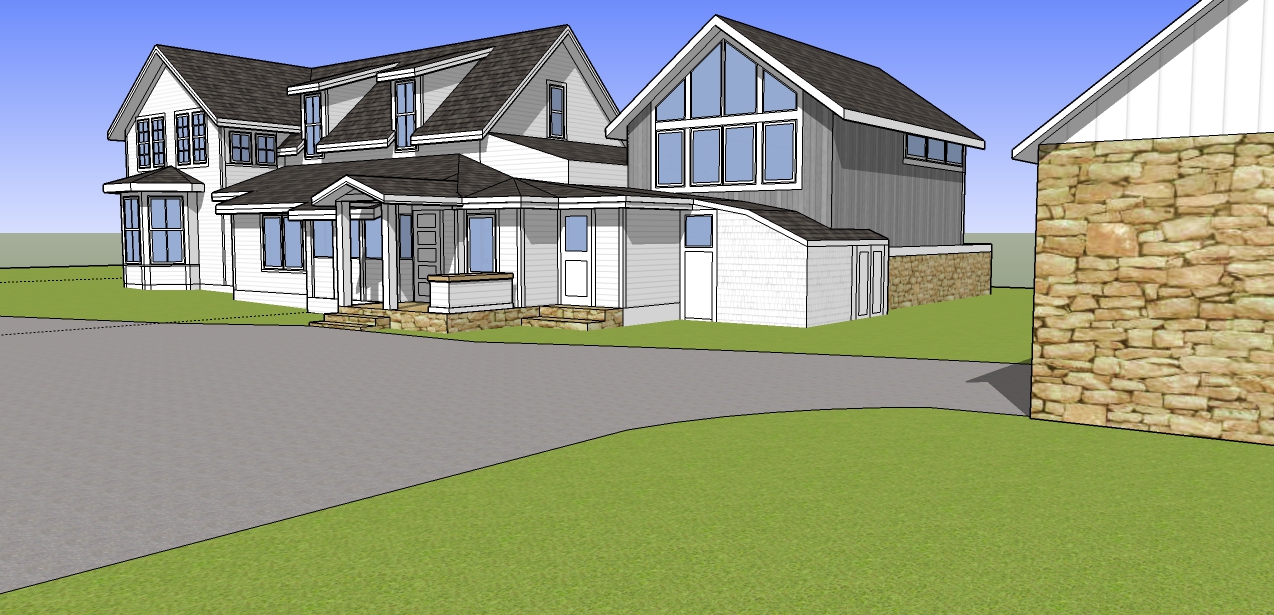

The image above is for a new house for a young couple in the Newlands section of North Boulder. It sits on a challenging corner lot with significant zoning restrictions. The rear of the lot has great views of the Mt. Sanitas foothills and the new house is designed to take advantage of those views while still engaging the surrounding neighborhood.

One of the projects that we are working on intermittingly is the renovation and addition to a historic farmhouse in Boulder. The farmhouse consists of an original older section and a number of past additions, including a series of enclosed porches. We are studying the practicality of providing new foundations, stablizing existing conditions and bringing the historic farmhouse into the future.

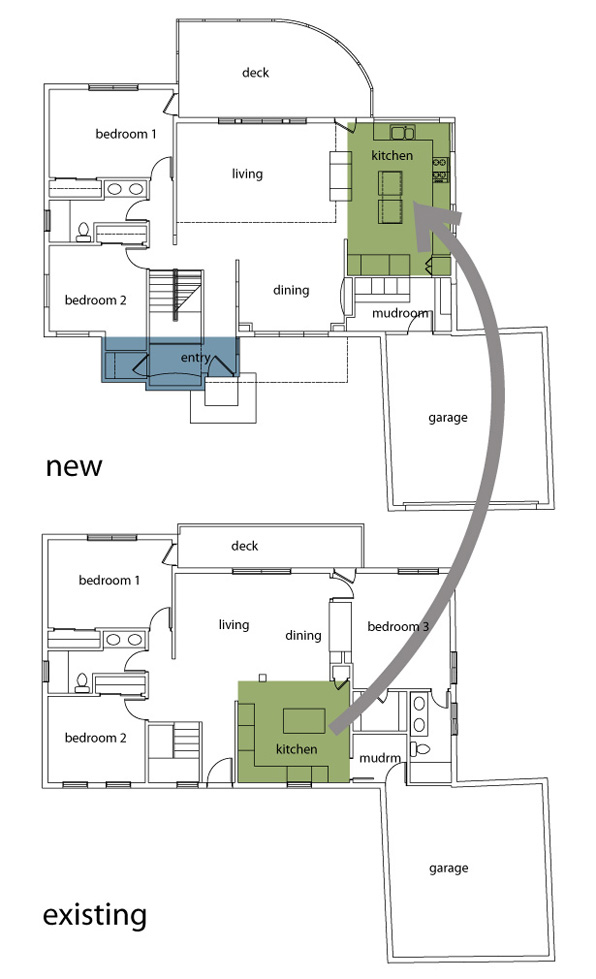

The projects above and below are in early stages of Schematic Design, both extensive re-ordering of existing houses.

We are taking on a couple of new projects every quarter or so and as long as they all stay in their proper phases, that allows us to have 5-4 projects in construction simultaneously. That allows us to be on site every day on every project - absolutely critical to doing design/build at the level of quality and invention that we think makes is all worth while for ourselves and our clients.

habitual patterns of use

We work on a lot of smaller projects that largely entail the internal reorganization of an existing house. Most often these are houses that were built in the 1960's and the current homeowners are struggling with small, awkward kitchens and houses that are more formally arranged than currently lifestyles are well suited.

Seeing the forest

New houses and restaurants are projects that allow for the most creative freedom, but it is these difficult spatial re-ordering projects that pose the greatest challenges and result in our greatest satisfaction. Most of these projects are hemmed in with zoning constraints and building restrictions, but the single largest constraint is often in the minds of our clients. Very often they have lived in the house for a number of years and although they are frustrated with it, it is very difficult for them to conceive of moving a critical function like the kitchen from one room to another. They have developed habitual patterns of use that make seeing the forest through the trees extraordinarily difficult.

I found this to be true in my own home renovation. Even as an architect, while living in the house it was difficult to imagine such a radical notion of demolishing and moving a kitchen across the house. Sitting with the drawings in front of me it was clearly the right move to make, but standing in the house it seemed daunting. And not just because of the associated cost and complexity that such a move would add to an already trying project, but because I had frankly become so used to getting my coffee and cooking so many meals there.

Running the possibilities

It is our habit that whenever we are faced with this kind of project we always run through a few exercises that test the possibilities of just these kinds of moves. What if the dining room flipped positions with the living room? How about if the entrance was on the other side of the house? Or, as in a recent project, what if the kitchen moved into the master bedroom?

I make it a practice not to talk about the potential changes to a house when I visit the property for the first time. For myself, it is the space and distance created while working in the studio that will most likely generate the most interesting solutions to a project, not walking around the house. It seems a bit counter-intuitive, but going to the actual site often makes the possibilities of a project less real, the potential of a project diminishes with the distance to the actual building.

In the dust, and clouds

In the end, it is a balanced attack on a project that provides the best answers and brings up the most interesting questions. As an architect, you have to go to the building and study it, but you also have to go to your studio and take it apart in your head. Architecture is practiced in the real world of walls and floors and dense materials, but it is best conceived in the imagination with paper and pencil, cardboard and glue.

Mullen Building, Denver

One of Denver's sort of hidden architectural gems is the Mullen Building, part of the Saint Joseph hospital complex.

Built in 1933, the Mullen Building was designed as a nursing school and dormitory by Denver architect Temple Hoyne Buell. Buell was from Chicago and like so many Coloradans, came out West for the treatment of tuberculosis. (I'm sure there is fascinating doctoral work out there on how some city's and regions were founded by a disease trajectory. Much of Boulder's early history is directly tied to health, well-being and the founding of sanitariums for TB victims.)

Temple Hoyne Buell

The Mullen Building is an art deco fantasy, more specifically it is one of the best examples of that strange stylistic hybrid that is vaguely Mayan/Aztec Revival Art Deco. The vertical bands of dark red brick blast up the facade and over the top of the building's parapet and are oddly akin to a Mayan headress, albeit executed in abstracted brick geometry. Frank Lloyd Wright's Hollyhock house in LA is probably the most well-known example of this kind of stylistic appropriation, but the Mayan Theatre, also in Los Angeles, built in 1927, is a building that may have influenced Buell. (Denver's Mayan Theatre of 1930 is a another example of Mayan Revival architecture, but one that is explicitly kitsch and although remarkable, likely not an influence for Buell)

Mayan Revivial movie theatres

The masonry work is truly remarkable. Almost entirely constructed from standard, modular bricks, the fanciful plasticity of the window bands and especially the entry surround, undulates and flows in brick units. It as if a very disciplined, obsessive kid spent a long, rainy weekend stacking their lego blocks, one after one. This kind of brickwork is often described as "waterfall" brick, but I hardly think that term does justice to the resolution of this work. Certainly the brick seems to cascade down the facade, but its simultaneous ascending dynamism sets up a delicate balance that is tempered by the soft, blond brick expanses. It certainly is the most exciting dormitory I have ever seen, an exuberant expression of what brick can do and how amazing an otherwise simple building can be. I’d like to imagine that long after they retired, the masons took their families by this building - “I made that.”