a lot of new projects in various stages of design, permitting and construction

Charles Haertling, Part One

I’ve written quite a bit about Boulder architect Charles Haertling over the nearly 20 years that I have lived in Boulder. His work has been a revelation and inspiration, a gentle reminder from the past to always seek out invention and never fall back to simplistic solutions. This Fall, I have been engaged by a property owner to actually do some work on one of Haertling’s houses, the Matheson House, high atop Marshall Mesa in South Boulder.

Projects in development

We have a number of interesting projects in process right now - great clients, great sites.

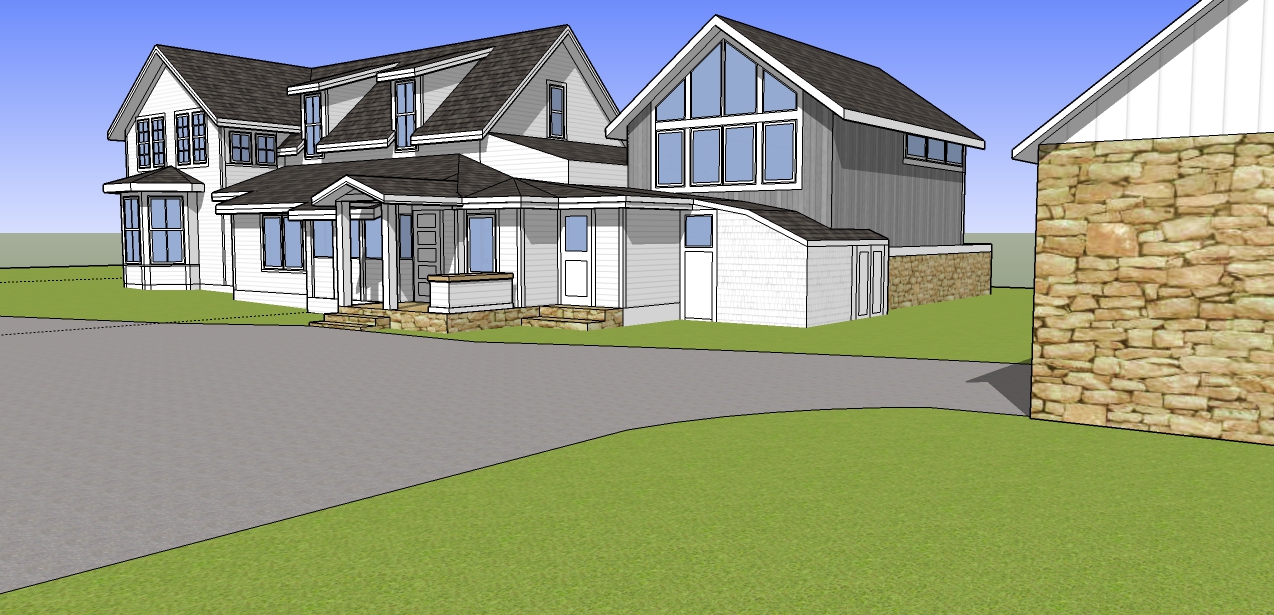

The image above is for a new house for a young couple in the Newlands section of North Boulder. It sits on a challenging corner lot with significant zoning restrictions. The rear of the lot has great views of the Mt. Sanitas foothills and the new house is designed to take advantage of those views while still engaging the surrounding neighborhood.

One of the projects that we are working on intermittingly is the renovation and addition to a historic farmhouse in Boulder. The farmhouse consists of an original older section and a number of past additions, including a series of enclosed porches. We are studying the practicality of providing new foundations, stablizing existing conditions and bringing the historic farmhouse into the future.

The projects above and below are in early stages of Schematic Design, both extensive re-ordering of existing houses.

We are taking on a couple of new projects every quarter or so and as long as they all stay in their proper phases, that allows us to have 5-4 projects in construction simultaneously. That allows us to be on site every day on every project - absolutely critical to doing design/build at the level of quality and invention that we think makes is all worth while for ourselves and our clients.

Price Tower

In northeast Oklahoma, just west of the Osage Indian Reservation, lies Bartlesville, home of Phillips Petroleum and Frank Lloyd Wright's only completed "skyscraper" building, the Price Tower.

The history of the Price Tower is long and complex and Frank Lloyd Wright's recycling of an earlier unbuilt tower design is well documented. It is all worth reading and a little study, but it really does not prepare you for a confrontation with the building itself. And even though by today's standard the building is not so tall and the motifs a bit dated, the building itself has a magnificent sculptural presence.

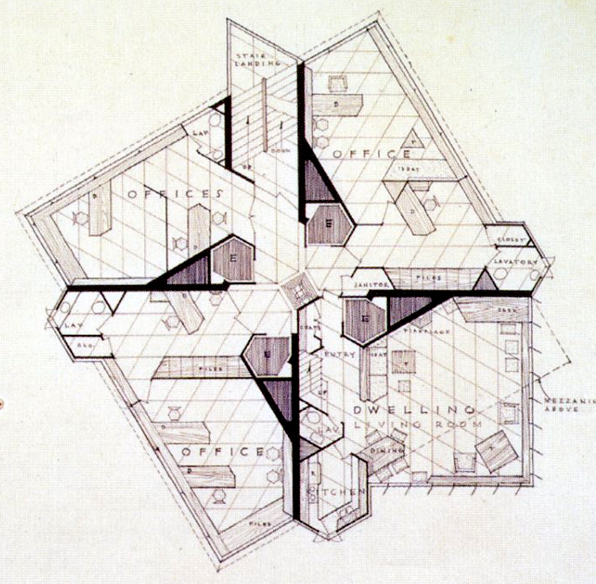

Designed for multi-purpose usage, the tower houses offices and residential space on each of its central floors. From the outside of the building, the horizontal slats and fenestration define the office spaces while the vertical louvers identify the residential portions. Instead of subdividing the building vertically and stacking one use exclusively upon the other, Wright and his client choose to intermingle the two, with only the base and top-most floors housing a single function.

Price Tower plan

It is often easy to forget how ornate Wright's work was when fully executed. The prairie houses he created had such a streamlined, simple and bold expression, that only actually visiting a work reveals the little carved panels and decorative embellishments. At the Price Tower, those embellishments take center stage as patterned, aged copper panels dominate the entire building and you will find smaller, more refined expressions on the interior.

Like so many of Wright's best works, the Price Tower is simultaneously bold and sculptural, refined and almost precious. It teeters on the edge of gilding-the-lily with its decorative motifs splashed across so much of the lower levels. But it is worth remembering the unlike so many of his modernist European contemporaries like Gropius and Mies, Wright believed in a very earthy kind of romantic sensibility and transcendent Beauty. In that sense, the Price Tower, like Wright himself, is a last echo of the nineteenth century passing through the end of the millenium. The Price Tower feels like a beautiful mash-up of Craftsman materiality and the Jetsons sci-fi retro-futurism.

Price Tower section

It's not exactly on the beaten path, but a visit to the building is worthy of a prolonged side trip. You can have a drink in the roof top bar or even stay in the boutique hotel created within, the Price Company's offices having long since removed themselves. And in Bartlesville you can get quite excellent chicken-fried steak, so go to it.

(Much of the historical info and imagery here is from The Price Tower, published by Rizzoli, Anthony Alofsin, Editor)

habitual patterns of use

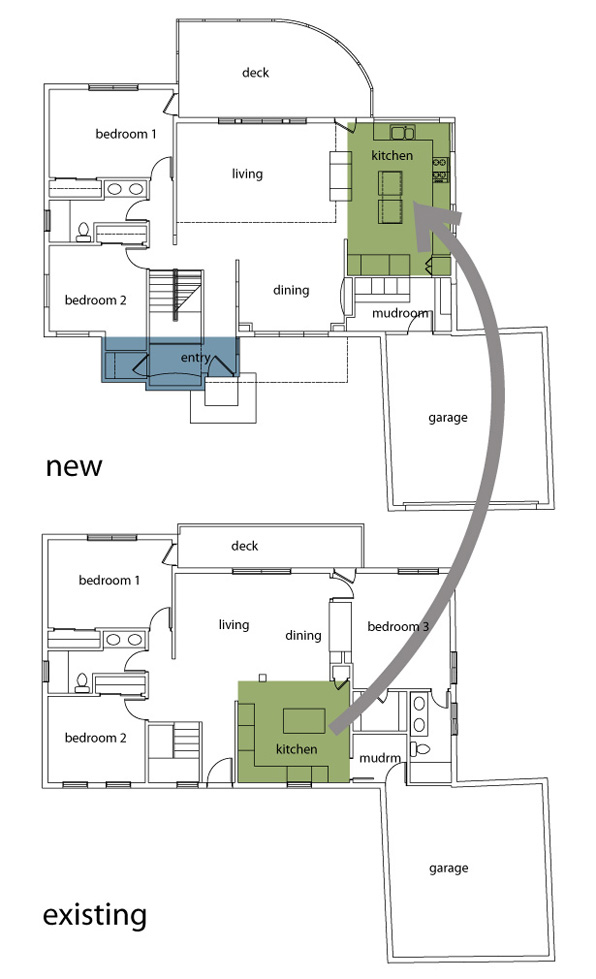

We work on a lot of smaller projects that largely entail the internal reorganization of an existing house. Most often these are houses that were built in the 1960's and the current homeowners are struggling with small, awkward kitchens and houses that are more formally arranged than currently lifestyles are well suited.

Seeing the forest

New houses and restaurants are projects that allow for the most creative freedom, but it is these difficult spatial re-ordering projects that pose the greatest challenges and result in our greatest satisfaction. Most of these projects are hemmed in with zoning constraints and building restrictions, but the single largest constraint is often in the minds of our clients. Very often they have lived in the house for a number of years and although they are frustrated with it, it is very difficult for them to conceive of moving a critical function like the kitchen from one room to another. They have developed habitual patterns of use that make seeing the forest through the trees extraordinarily difficult.

I found this to be true in my own home renovation. Even as an architect, while living in the house it was difficult to imagine such a radical notion of demolishing and moving a kitchen across the house. Sitting with the drawings in front of me it was clearly the right move to make, but standing in the house it seemed daunting. And not just because of the associated cost and complexity that such a move would add to an already trying project, but because I had frankly become so used to getting my coffee and cooking so many meals there.

Running the possibilities

It is our habit that whenever we are faced with this kind of project we always run through a few exercises that test the possibilities of just these kinds of moves. What if the dining room flipped positions with the living room? How about if the entrance was on the other side of the house? Or, as in a recent project, what if the kitchen moved into the master bedroom?

I make it a practice not to talk about the potential changes to a house when I visit the property for the first time. For myself, it is the space and distance created while working in the studio that will most likely generate the most interesting solutions to a project, not walking around the house. It seems a bit counter-intuitive, but going to the actual site often makes the possibilities of a project less real, the potential of a project diminishes with the distance to the actual building.

In the dust, and clouds

In the end, it is a balanced attack on a project that provides the best answers and brings up the most interesting questions. As an architect, you have to go to the building and study it, but you also have to go to your studio and take it apart in your head. Architecture is practiced in the real world of walls and floors and dense materials, but it is best conceived in the imagination with paper and pencil, cardboard and glue.